Picture with a Thousand Pieces:

Archival Research on Missionaries and the Waorani

(2017 BGC Archival Research Lecture, delivered by Dr. Kathryn Long on October 5, 2017 at the Billy Graham Center n Wheaton, Illinois, USA. Abridged

for online readers)

Introduction

Thanks to

the BGC Archives for the invitation, also for prayers and encouragement from

many in the audience during a challenging year.

Tonight, I

want to talk about using archives, and specifically the Graham Center Archives,

to do research for a book I’ve written that is in the final stages of editing

(I hope!). Its title is God in the Rainforest: Missionaries Among

the Waorani in Amazonian Ecuador. It traces the story of missionary

interaction with the Waorani, an isolated group of indigenous people in the Ecuadorian

Amazon, between 1956 and about 1994.

Contact between missionaries and the Waorani, then called “aucas,” began

with an event familiar to many people in this room: the deaths of five young

missionaries in 1956, speared as they tried to make peaceful contact with the

Waorani. Two years later, two missionary women—Elisabeth Elliot, the widow of one

of the slain men and Rachel Saint, the sister of an another, with the help of a

Waorani woman named Dayuma—successfully contacted the Waorani and began efforts

to introduce them to Christianity and to help end the violence that was

destroying their culture.

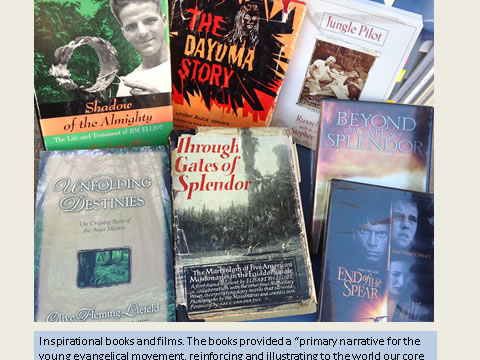

[Slide 1] The

sacrificial deaths of the five men and subsequent efforts to Christianize the

Waorani became the defining missionary narrative for American evangelicals

during the second half of the twentieth century. It certainly was the most

widely publicized. Here are a few of the books, and, more recently, the films,

that told the story. Looking back 40 years later, Christianity Today magazine described the story as serving at the

time as a “primary narrative for the young evangelical movement, reinforcing

and illustrating to the world our core ideals.” CT, Sept. 16, 1996.

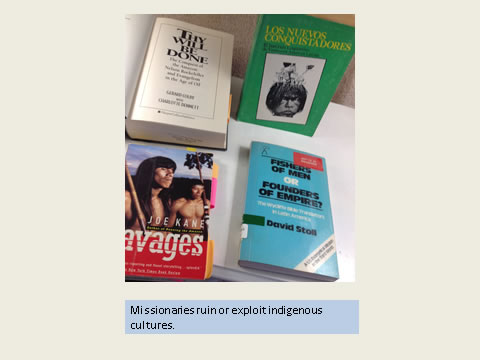

[Slide 2] While

many evangelicals—certainly not all, but many—cherished this inspirational

narrative, a significant number of people outside the evangelical fold

criticized the missionaries. They viewed

what happened in Ecuador, especially efforts to Christianize the Waorani, as

“Exhibit A” of how missionaries destroyed indigenous cultures. There was a need for a book that would

address these issues and update the missionary/Waorani story. Also, there were

missionaries, especially staff from the Summer Institute of Linguistics, but

others as well, who had worked with the Waorani between the late 1960s and the

mid-1990s, whom most people had never heard of.

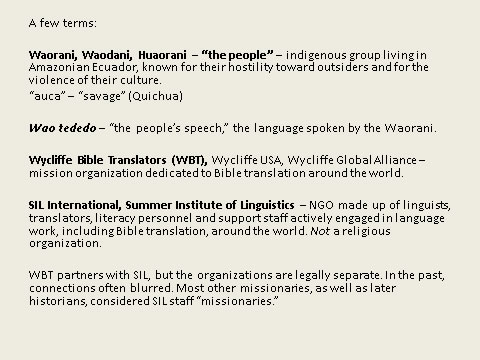

Before I

launch into the main part of the lecture, let me quickly go over a few

important terms: [terms on S3]

I wanted the

story to be based on original sources, for the most part unpublished, to get a

fresh perspective. T his wasn’t always possible—in the end the book is based on published

sources, interviews, private papers, and archival materials. Still archival

sources played an important role. Fortunately for me, many the sources I needed

were housed here at the Graham Center Archives and a few at the Wheaton College

archives. Here, for example, is a sample of some materials housed here that

include sources related to missionaries and the Waorani:

Collection 136: Records of Mission Aviation Fellowship

Collection 277: Papers of Jim Elliot

Collection 278: Papers of Elisabeth Howard Elliot

Collection 349: Papers of Clarence Wesley Jones

Collection 599: Ephemera of the “Auca Incident

Collection 657: Papers of Kenneth Fleming

Collection 670: Papers of Kathryn (Rogers) Deering

Collection 684: Papers of Herbert I. and Colleen Collison Elliot

Collection 687: Papers of Theophilus Edward Jr. "Ed" and Marilou G. Hobolth McCully

Collection 701: Papers of Olive Ainslie Fleming Liefeld

Accession 08-36: Papers of M. Catherine Peeke (closed)

For the book, I

also did research in collections that are not here at Wheaton, especially the

archives of the Summer Institute of Linguistics and the papers of SIL’s

founder, William Cameron Townsend.

I never

tried to total up the number of actual documents that I read from these and

other collections—counting letters, reports, notes, transcribed interviews—I

would guess the total would easily be more than 2,000 unpublished documents.

[S5] This

brings me to tonight’s lecture, “Picture with a Thousand Pieces.” I chose this

title because for me the process of using archival materials to shape a historical

narrative, to tell a story, seemed a lot like putting together a large and

complicated jigsaw puzzle—the contents of a letter might represent one piece of

the puzzle. The response to that letter from someone else might be another

piece. A memo from other people could be yet another. What I’d like to do tonight is to sample a

few sections of this puzzle that is the history of missionaries (and American

Evangelicals more broadly) with the Waorani to show you some of the rewards as

well as the frustrations and challenges, of this kind of archival research.

1. Records of Mission Aviation

Fellowship

The first

example comes from the Records of Mission Aviation Fellowship and involves

reports and letters from two pilots: Johnny Keenan and Hobey Lowrance. If you

know this story, you probably knew Nate Saint was a part of Mission Aviation

Fellowship. What you may not have known

was that MAF continued to play a significant role in the Waorani project even

after Saint had been killed.

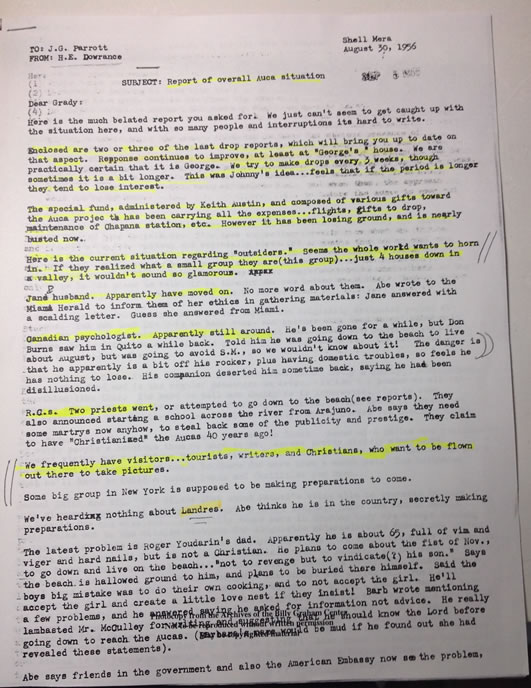

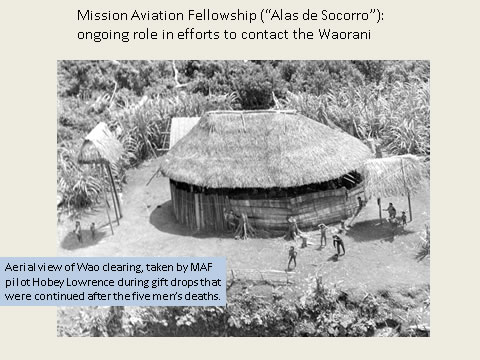

{S6]

Pilots did

fly overs and dropped gifts every couple of weeks between February 1956 and September

1958. This picture was taken by MAF

pilot Hobey Lowrance, not Nate Saint. The letterabove summarizes some

of the activities during the first six or seven months after the men’s

deaths. Publicity brought a lot of

people to the rainforest.

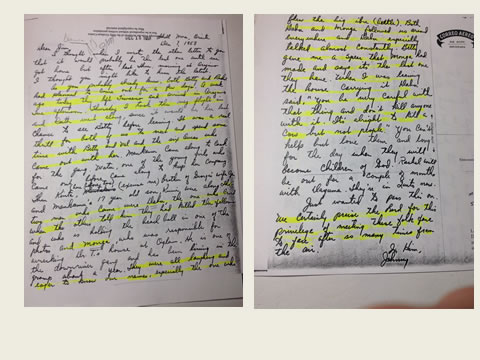

The above slide [S7] highlights a handwritten letter Johnny Keenan sent to MAF

headquarters about meeting the Waorani in December 1958 when Elisabeth Elliot

and Rachel came out of the rainforest for a break after making peaceful

contact. A few Waorani came with

them. Keenan had an opportunity to meet

some of the Waorani whose clearing he had flown over so often. This is a .pdf

of his original letter.

The paragraph below

[S8] shows how, given some context, that letter became a part of my manuscript.

God in the Rainforest:Two days after they [the Waorani] arrived, pilot Johnny Keenan, accompanied by his wife, Ruth, made the regular “vegetable run” to Arajuno. Despite official MAF reluctance, in May 1957 Keenan had invited Elliot to fly with him on a gift drop over the Wao clearing, an experience that had strengthened her desire to meet the Waorani face to face. Now it was Keenan’s turn for a close encounter with the Waorani he had flown over so often.

“Kill a Cow but not People”

“They were all laughing and eager to know our names,” he reported, “especially [the name of] the one who flew the big ebo (‘beetle’).” Dabo and Monca followed the pilot wherever he went, Dabo talking almost constantly, completely unfazed by Keenan’s inability to understand anything he said. Before the Keenans left, Betty gave Johnny a spear Monca had made, telling him it was the last one the group had left. As Keenan walked out the door of the house, carrying the spear, Dabo spoke to him (Elliot translating). “You be very careful with that thing and don’t kill anyone with it,” he said. “It’s alright [sic] to kill a cow but not people.” Dabo’s statement was widely publicized in the missionary community and later in the US. To evangelicals it was a miracle—and sign of answered prayer—to hear a savage Waorani saying, in effect, “Thou shalt not kill” to an American missionary pilot.

This is a

small sample of what I wrote about MAF’s involvement in the Waorani mission,

but I hope these examples help to show how the MAF’s records provided the

information to more fully develop MAF’s role in the Waorani project.

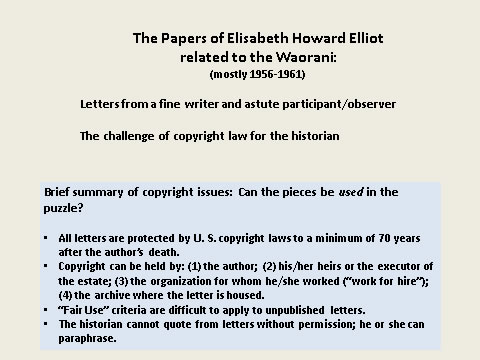

II. The Elisabeth Howard Elliot

Papers

[S9] A

second BGCA collection that I consulted extensively were the papers of

Elisabeth Howard Elliot, a key figure in the early years of missionary outreach

to the Waorani and one of the most significant authors in shaping public

understanding of the Missionary/Waorani encounter, particularly through her

books, especially Through Gates of

Splendor, Shadow of the Almighty,

and The Savage My Kinsman.

Elisabeth

Elliot gave the first of her papers to the BGC Archives in 1985. Initially the

collection consisted mainly of materials related to her books, supplemented by

an oral history interview with Elliot conducted by Bob Shuster. At the time, copyright

to the manuscripts and other materials in this collection was retained by

Elisabeth Elliot, with her permission required until 2006. Additional

materials—most important among them, Elliot’s personal letters to her parents

and other family members—were added to her papers between 2004 and 2016.

Elliot’s

papers are important, among other things, because she was an astute observer

and a great writer. But to understand the challenges in using them, it’s

important to understand the basics of U.S. copyright law. Copyright law determines

whether the pieces the historian finds in archives can be used in the puzzle. Here are the basics:

• All letters, no matter who writes

them, are protected by U. S. copyright laws to a minimum of 70 years after the

author’s death.

• Copyright for unpublished materials

can be held by: (1) the author; (2) his/her heirs or the executor of the

estate; (3) the organization for whom he/she worked (“work for hire”); (4) the

archive where the letter is housed.

• The criteria for “Fair Use” are difficult

to apply to unpublished letters. “Fair use” refers to the guidelines that

enable writers or researchers to publish some copyright materials without

permission.

• The historian cannot quote from

letters without permission; he or she can paraphrase.

MAF papers

are records of an organization; most letters were written between various staff

members as part of their jobs and so were considered “work for hire,” copyright

MAF. Also, when MAF put their records in

the BGC archives, they gave the archive limited ability to grant copyright

permission. With permission, researchers like myself can quote from those

letters.

In

contrast to the MAF Records, Elliot’s papers are a personal collection, belonging

to her or her estate, not work for hire. There are a couple of reasons for this:

1)

Elliot

wrote most of her letters to family and friends, and personal letters are

usually not considered “work for hire.”

2)

Also, because of the influence of her first

husband, Jim Elliot, Elisabeth went to the mission field under the sponsorship

of Christian Missions in Many Lands, the sending agency for a loose coalition

of independent gatherings or assemblies that came to be known as the Plymouth

Brethren. The Brethren rejected traditional denominations or any other

organizational structure that they didn’t find in the New Testament.

Missionaries were responsible to their home assemblies, but for all practical

purposes were independent agents on the mission field. So Elisabeth Elliot was not a part of an

administrative structure such as that of Mission Aviation Fellowship.

As

a result, the papers belonged to EE, and even when she chose to house them in

the BGC archives, she retained the copyright.

At the time of Elliot’s death in 2015,

copyright to her papers shifted to her estate. That left the executor of the

estate with the authority to grant copyright permission. My hope was to get

permission from Mr. Gren to quote his late wife’s letters.

Most of my

research involved the letters EE wrote during the six-year-period between her

husband’s death in 1956 and her decision to leave the mission to the Waorani in

1961. Elliot wrote about her sense of calling to the Waorani after Jim’s death;

about life among the Waorani during the first years after contact; and about

her relationship with missionary colleague Rachel Saint, Nate Saint’s older

sister.

Meals were another challenge in cultural adaptation. The Waorani ate rapidly and with plenty of sound—“a great slurping and sucking.” In three or four minutes a group of men could demolish a pile of plantains and a pot of meat, without even a bare minimum of the social niceties expected by Westerners. When men we re in the clearing and the hunting was good, monkey meat was standard fare. Elliot found it disconcerting to watch the creatures, shot with blow gun and poison darts, first singed to remove the hair, then boiled. They looked too human. The Waorani considered monkey heads a great delicacy, and skulls were licked and sucked with enthusiasm, including in a “mouth to mouth” position. After five or six weeks, Rachel confessed she had overcome her “prejudices” enough to eat some of the brains herself. However, she still “left the sucking of the eyes to Acawo.”

From God in the Rainforest.

Kinsman, 120; Dayuma Story, 238, 239.

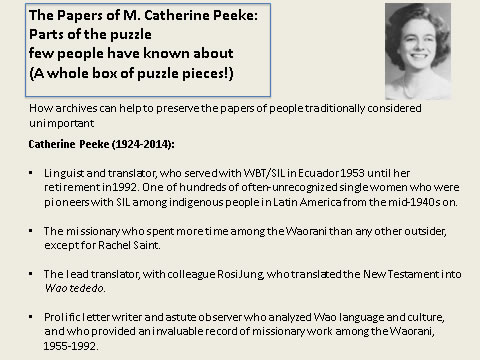

III. Papers of M. Catherine Peeke

Finally, I want to talk

about Catherine Peeke and her papers. She was the linguist whose photograph was

on the postcards and other materials advertising this lecture.

[S11] Catherine is

little known outside of the Summer Institute of Linguistics circles—and even by

many within SIL—but she was one of two linguists (along with German healthcare

worker and linguist, Rosi Jung) who translated the New Testament into Wao Tededo.

By the end of her life

Peeke also was one of perhaps a handful of outsiders fluent in the Wao language

and who really understood the Waorani and their culture, although she always

downplayed her ability. She served with the Summer Institute of Linguistics and

the Wycliffe Bible Translators for more than forty years, and spent at least

twenty-five years working directly with the Waorani. She was with Rachel Saint

in 1955 when Rachel met Dayuma; she was eyewitness to more of

Waorani/missionary interaction than anyone except Rachel Saint.

She was part of a team

of SIL staff members who worked with the Waorani beginning in the early 1970s.

Catherine Peeke and

Elisabeth Elliot were contemporaries—Cathie was two years older than Betty and

died two years earlier. Elliot was famous among evangelicals in the US and

elsewhere for her courage and faith; Peeke accomplished what Elliot originally

had hoped to do as a linguist/missionary living and working among the Waorani.

In the context of constructing a picture with

a thousand pieces—if the MAF Records and Elisabeth Elliot’s papers each

represents a portion of the picture, Catherine Peeke’s papers represent maybe

half the box of puzzle pieces, and they help to create a part of the picture

few people have seen.

Cathie Peeke was born

and raised on a farm outside of Weaverville, North Carolina, not far from

Asheville. She was a quiet, introverted person, who laughed about what she

described as her “hillbilly accent” from the North Carolina mountains. In 1949,

she joined the Wycliffe Bible Translators.

After training, and then a few years in Peru, Catherine was assigned to

Ecuador in 1953 and helped to establish SIL in that country. She had a gift for languages, and she quickly

became a language consultant for the Ecuador SIL—she would visit the different

translation teams in the country and help them to trouble-shoot their problems

with indigenous languages. In the early 1960s, she decided to pursue a Ph.D. in

anthropological linguistics at Indiana University.

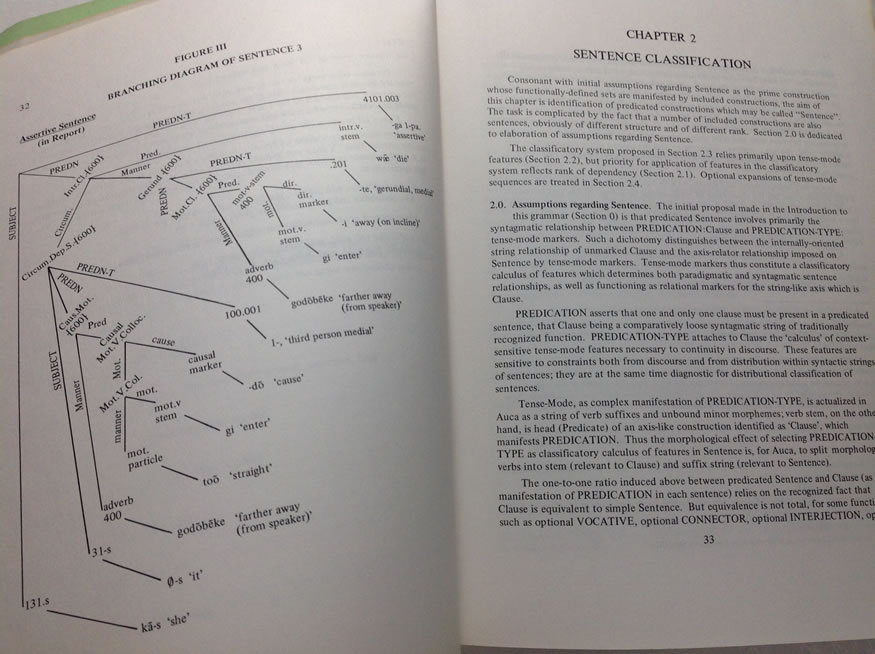

Her dissertation was a

grammatical analysis of the Wao/Waorani language. She had learned a little of

the language from Dayuma and Rachel.

Elisabeth Elliot gave Peeke her language notes, and while Peeke was in

grad school, she did linguistic research in Ecuador among the Waorani in

Tewaeno, where Rachel Saint lived.

[S12] It turned out

that Wao tededo (“the people’s

speech”) is a linguistic isolate—unrelated to any of the other Amazonian

languages around it, or any other language anywhere. Catherine figured out how

the language worked, analyzing its grammar. She usually downplayed her

accomplishment, saying it was easier to understand Wao tededo than to speak it, although she did that well, too. She

received her Ph.D. in June 1968. From then until her retirement in 1992 she

worked full-time with the Waorani. For the last twelve or 13 years, Catherine

and her co-worker, German linguist Rosi Jung, and about twelve Waorani

assistants translated the New Testament into Wao tededo.

Her story and the

collection of papers that tell much of that story illustrate, among other

things, how archives provide a place to preserve the records of people whose

papers traditionally have not been considered worth saving. There’s a difference between Cathie Peeke and

the MAF pilots I mentioned earlier.

Hobey Lowrance and Johnny Keenan may not have been fully included in

earlier versions of this history, but their letters were available. In

Catherine’s case, nobody thought her papers—or the papers of other pioneering

missionary women like her—had much value.

Like Elisabeth Elliot—although their styles

were different--Catherine Peeke was a good writer. And she wrote a lot. During the years she was in Ecuador, Peeke

wrote a letter home to her family in North Carolina every week, usually to her

mother or her sisters. Of course, they contained family news, but also news

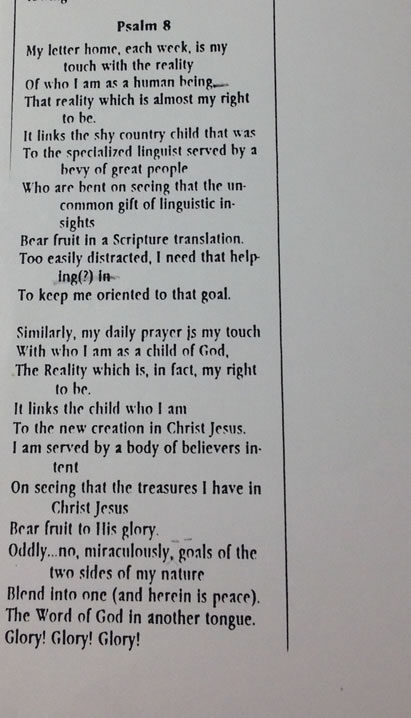

about her life and work. At some point—I don’t have the date, she wrote a

personal “psalm” expressing the importance of the letters home to her identity,

alongside her calling to translate the New Testament [S13].

Shy country girl, Committed Christian, Linguist and Translator

To Glorify God

Catherine’s papers are

a rich record of what it was like to live among the Waorani; what it was like

to be a single woman and a missionary linguist in the Ecuadorian Amazon; what

it was like to be a little-known participant in one of the most famous . . .

and on occasion controversial . . . missionary ventures of the twentieth

century. . .. what it was like to translate the New Testament into the Wao

language . . .

Here are some samples

of the many kinds of materials in the Peeke Papers:

·

Report on translation and on the spiritual response among the

Waorani.

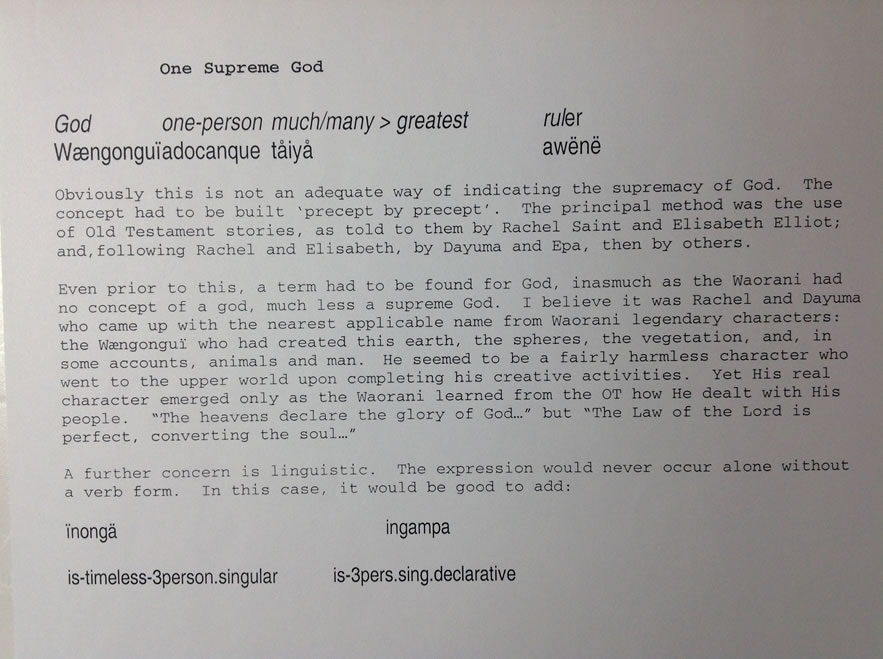

Translation choices in deciding on a word for God, then communicating that this was the one, supreme God

·

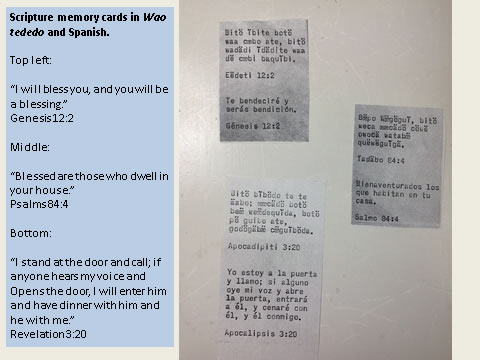

Explanations of translation work. [S14]

·

Translation memory cards. [S15]

·

Prayer requests that included balanced descriptions of Wao

believers. Catherine respected the Waorani and knew some of them quite

well. Her observations and descriptions

help make the Waorani multi-dimensional human beings

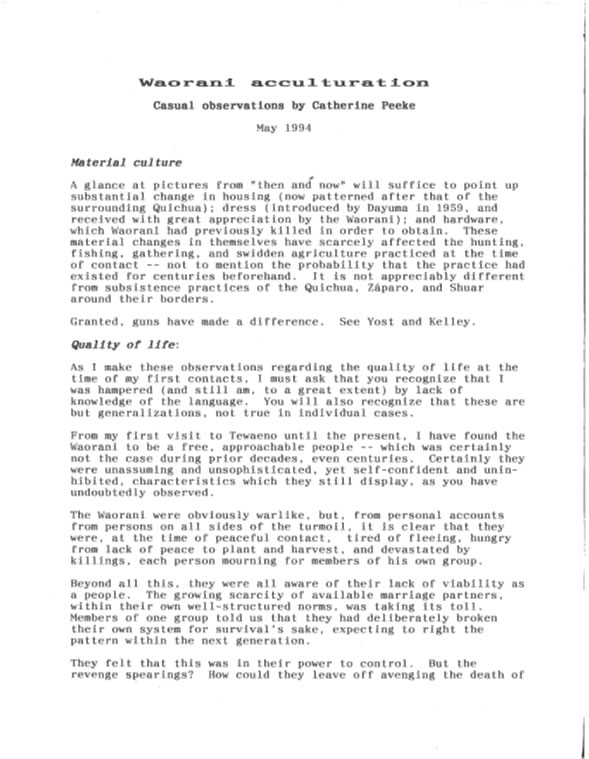

Peeke's reflections on Wao culture, in response to outside inquiries

Reflections on Wao culture. [S16]

The good news is that

Catherine kept everything. The bad news was that she wasn’t particularly

organized. When I first met Catherine,

her papers were in boxes, file cabinets, drawers—wherever she could put them in

the upstairs bedrooms of family farmhouse where she lived. She put most things

in file folders or manila envelopes but, again, often in no order or subject,

and the label on the folder didn’t necessarily match what was in the folder.

I spent a week at

Catherine’s home in 2005, going through papers and taking notes like crazy. We

corresponded by email over the next few years.

Then in 2008, she sent me an email saying she was downsizing. Did I want any of her papers? Otherwise—apart

from a few things she might give to colleagues, the bulk of the papers would

probably end up tossed in a ditch. At that point, the Summer Institute of

Linguistics had a linguistics archive—a place to keep documents related to the

academic and scientific aspects of translation work—but they did not collect

the papers of individual staff members (that has changed in recent years).

I contacted Bob Shuster

and asked him if the BGC Archives would be willing to give the Peeke Papers a

temporary or, if needed, a permanent home (they would). Bob gave me eight or

nine archive quality storage boxes, and my sister and I made a quick trip to

North Carolina to collect Catherine’s papers. They’ve been here in the archives

ever since with the stipulation that I could use them as long as I needed to (neither

Catherine nor I ever imagined it would be this long). At that point, if SIL had

a place for them, they would be sent there. If not, they would stay in the

Graham Center. Based on the accession agreement with Peeke, these papers are

not yet open to the public. Probably the

Summer Institute of Linguistics will determine when that will happen.

Nonetheless, even if Catherine’s papers aren’t yet open, they are safe. They’ve been preserved.

* * *

I want to conclude with

two brief documents, each of which represents a small piece of the

missionary/Waorani puzzle but an important one.

They also offer insights into mission work and the value of archives.

Particularly during the

1970s and the 1980s, SIL staff were criticized for their work among the Waorani,

criticisms that fed into the broader debates about missionaries and indigenous

cultures. In more recent years, scholars and others have begun to appreciate

the positive contributions missionaries have made.

Still, even some

Christians have raised questions about the genuineness of Wao Christianity

because aspects of their ecclesiology or doctrine don’t seem quite right, at

least in the eye of the observer.

What struck me in reading Catherine’s papers—apart

from all the information that’s there—is that sometimes, with no fanfare,

missionaries and indigenous people simply become friends and love each other.

This was the experience

of Catherine and one of her language assistants Oba, Yowe’s wife. Yowe and Oba

were among the first Waorani to become Christians. Catherine and Oba worked together for

years—Catherine praised Oba’s efforts to make sure Catherine’s translation was

grammatically correct, even if Oba wasn’t as strong with comprehension. When

Catherine retired and left the Wao village of Tewaeno after the New Testament

was translated, Oba was so upset to see her go that she couldn’t come to the

airplane to say good-bye. A few years

later, it was Peeke’s turn to grieve when news came that Oba had died in a

chicken pox epidemic. Remembering her friend and the years they had known each

other, Catherine wrote the rough draft of a poem. [S17]

Cathy and Oba: Friends who loved each other:

It was a lament for a dear

friend . . .remembering Oba as a young mother, a hard worker, a prayerful

translation assistant, a dear person, a woman certain about cosmology as the

Waorani understood it.

The poem ended with the

cry, “O Lord, I should have gone first” from the 69-year-old Peeke before

Catherine surrendered her grief to God’s perfect will.

“They will know that

you are my disciples if you love one another,” Jesus said. This love can be a reality on the mission

field as well as at home.

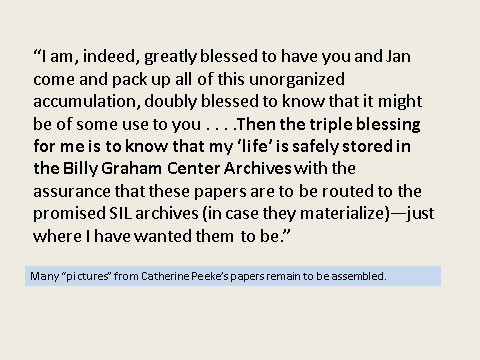

Finally, here is an

excerpt from an e-mail Catherine Peeke sent, thanking my sister and me for

helping to preserve her papers. It

summarizes some of my own gratitude for places like the BGC Archives:

[S18]

Catherine Peeke’s life

was much more than her papers, of course, but the BGC Archives and the SIL

archives have made (and will make) it possible for the record of her life and

of the Waorani she worked with to be preserved for future researchers and

historians.

Many “pictures” remain to be assembled.

Thank you.

--Kathryn Long